|

CNC ROBOTIC ABSTRACT PHOTOGRAPHY

About RC-ACR, a remotely operated camera control system

and other robotic cameras designed and built by Mark Lindquist.

Remote Control Articulating Camera Robot

(RC-ACR)

By Mark Lindquist |

January 23, 2016

© Lindquist Studios All Rights

Reserved

I began building a CNC Photography Robotics system based on a large

robot I had designed and built in the late 1980’s

called OPRA (Omni Positional Remote Articulator)

that is controlled by 90VDC open-loop controllers.

I built a consolidated control panel in order to manage all the robots in my

studio at the same time.

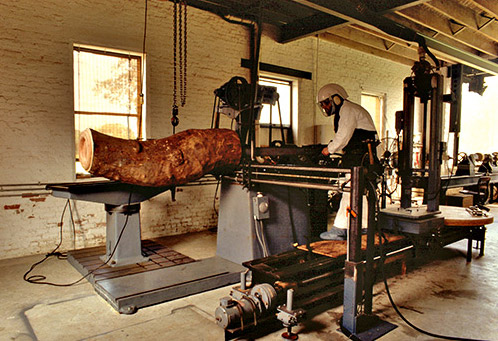

OPRA was designed and built by me in 1989, with fabrication

assistance from my then studio assistant Roger Paph.

(See control panel I built in the center, background, below).

I designed it to help me position wood being sculpted so that I could

sit while working.

I had had a severe automobile accident and couldn’t bend well, so I

built the robots to help with ergonomics.

Mark Lindquist sculpting wood being held and positioned by his robot

OPRA (controller in background.)

Photo: John McFadden

Mark Lindquist with his robot ASTRO (Assigned Specific

Task Robotic Operative), (background) - Lindquist

Studios circa 1990

Photo: Roger Paph / Lindquist Studios

90 volt DC controllers are fantastic, especially when they are

four-quadrant controllers, that enable “plug reversing”.

Mark Lindquist working with his robotic control panel in studio while

being filmed for the movie: Soul’s Journey.

Photo: John McFadden

In the nineties I began experimenting with OPRA to use it with

photography. Basically, I created an end-effector holding system that

would enable me to put a camera on it instead of a bowl. A little big

and heavy, but worked well.

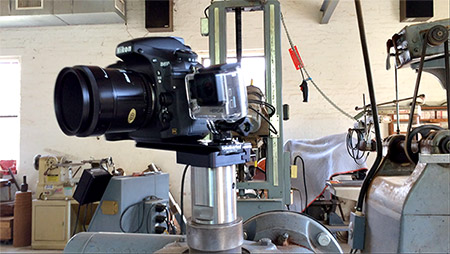

Here at the beginning of the RoboCam project, the Nikon D810 camera is

mounted on OPRA.

This worked well, but couldn’t be repeatable as it was controlled

by DC motor controllers

and as Matt Cardwell put it, “would need a crane to position it in the

field.”

My youngest son, Josh Lindquist, who has been a software design engineer

at Microsoft for 18 years

encouraged me to automate OPRA to be able to get repeatability.

So I began designing and building a stepper motor system to be

lightweight, portable, and versatile.

I started by wanting to buy a Cognisys system. When I found out that the

Cognisys system would not run at the speeds

I calculated I needed, I began to investigate building a miniature

version of OPRA. OPRA worked beautifully, ultra smooth, exceptional

stability, and a joy to use. Unfortunately, REALLY heavy.

About that time, some collector friends, Dr. and Mrs. Matthew Cohen

bought a piece of my sculpture as a kind of grant to enable me to buy or

build the robotics I needed to automate my existing photographic process

of motion blur.

I very much appreciate Matt and Leslie’s contribution to the project. I

spent 3-4 times what they

had given for the sculpture in the end, and I’m still going, but I’m

slowing down.

I began by attempting to build a system that was similar to the Cognisys

rotary tables which ran at an 80:1 ratio.

After lengthy discussions with Matt Cardwell, (Cognisys)

I realized I had to build my own system.

I started by purchasing a Cognisys Stackshot controller and a stackshot

extended rail.

Not being able to use their rotary table, which was a disappointment, I

found several special

miniature gear heads on ebay and after buying them realized that the CNC

stepper motors

wouldn’t fit the housings and they would need to be modified.

I contacted Jeffery Woodcock, (picengrave)

a local master machinist

who currently owns and operates a laser engraving software business.

Jeff has done machine and CNC work for me over the years. We’re talking

serious skills.

Jeff modified several gear heads adapting them to accept Nema 17 stepper

motors and hybrid steppers.

It’s small, precision work, and as I found out after re-working several

in order to accommodate

different motors or adding sound dampening components, it’s tedious,

demanding work.

All of the design work was experimental. I’d try one design only to

find out the gear head wouldn’t

hold the camera in certain positions, or it would overheat. Back to

the drawing board.

Perhaps the biggest problem I ran into was oscillation or sympathetic

vibration, called resonance.

This was most prevalent in the low to mid-band frequencies.

Matt Cardwell helped me with that, suggesting sound dampening means be

imposed.

I used industrial felt in some cases as well as vulcanized rubber

and inertial dampers. The inertial dampers are tricky. They either work

or they don’t work.

The one constant is that they are expensive, even when bought new or off

of eBay.

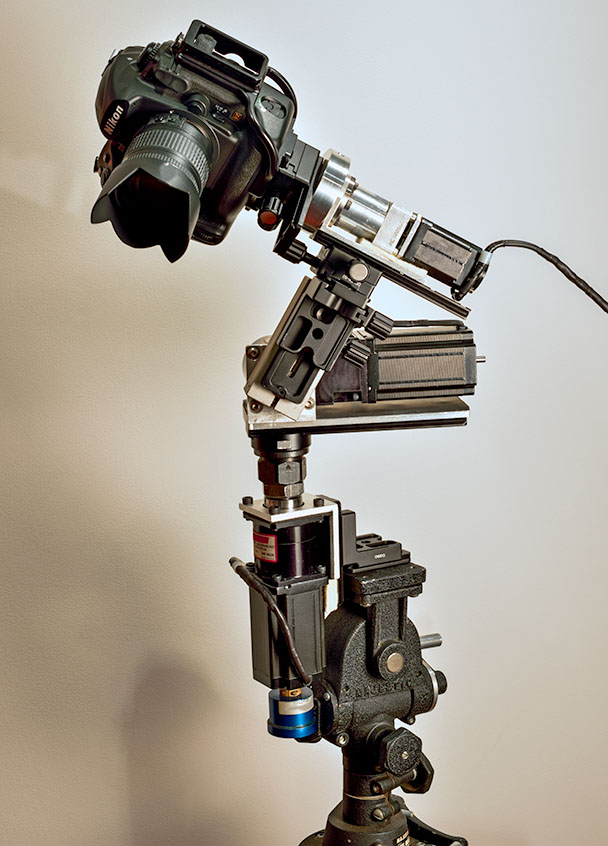

Here is the first working prototype with gear heads adapted and modified

with inertial dampers:

Jeff Woodcock adapted the gear housings to accept the hybrid

stepper motors he introduced me to

and contributed a very nice CNC manufactured base (to the right in the

photo above) to an old

very expensive gearbox I had. He also threaded the shaft. In each case,

I built

the brackets and designed a mounting system around the Arca style quick

clamp photo camera holding system.

Notice the yellow inertial dampers that I adapted to the incoming and

outgoing shafts.

This was the initial prototype. After all this work, it turned out that

the 1:1 gearing, while it gave me the speed I thought I needed could not

hold the weight of my camera when in a rotated position. Increasing the

torque held, but during a shooting session, prolonged use resulted in

overheating. Additionally, it turned out that even as precise as these

gear heads are, they still have backlash, which becomes magnified with

weight.

So as it stands, unfortunately, the lightweight RoboCam won’t work for

use with my Nikon D810 or D3s cameras

which is what I designed it for. I understand how this happens -

design something based

on a theory and create a prototype. It either works or it doesn’t.

So I keep the “lightweight model” with hope that one day a new model

camera will come out that

will do everything the D810 will, but will be super lightweight.

I very much appreciate Jeff Woodcock’s metal lathe work adapting stepper

motors to my gearheads.

It was very helpful to me

in the early phases of developing my prototype.

When I began the project, I was recuperating from having major surgery.

I simply couldn’t work.

Jeff Woodcock’s help with the project enabled me to get started, and

when I saw his work,

I understood the requirements of working on a small scale and began

gradually, to do the work myself,

particularly as he encouraged me to do so. I appreciate everything he

did helping me with my prototype.

Some of those early components are still in use in the current model. Jeff

also did a brilliant

DC motor mount on a studio camera stand I have with an elevation column.

I gradually moved on to build a much heavier system with much heavier

gearboxes that will hold the camera.

I’m still working on it and continuing to develop advances doing the

machining myself.

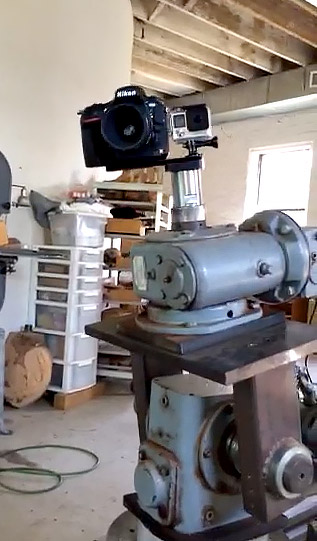

This is the second major prototype utilizing Nema 23 Hybrid Stepper

Motors, intermediary gear reducers

sound attenuating dampers and inertial damper. Majestic Tripod,

Nikon D3s camera, with 50mm Nikkor lens.

This is somewhat portable to be able to take in the field, although not

a "back-packable rig" yet.

The arm will fold back down parallel with the motor shaft for 360 degree

panos.

RC-ACR I- Lightweight portable system by Mark

Lindquist - 2015

I have made some images with the evolved system that I have built

subsequently.

Early images from the original prototype showed promise

but didn’t compare to the work done by hand over 15+ years of

development.

Early Robotic Camera Abstract Image by Mark Lindquist 2015

Remote Control Articulating Camera Robot

Abstract Image (RC-ACR) by Mark Lindquist, Late 2015.

Copyright ©

Lindquist Studios 2015/2016

All Rights Reserved

I learned a little metal turning/machining from my father,

woodturning pioneer Mel Lindquist when I was younger.

I wish I had paid more attention to that when he was alive. He was

at one point in his career a master machinist at

General Electric Company in SanJose, CA, then in Schenectady, NY.

He eventually became head of

Quality Control in his department and was a fellow of the American

Society of Quality.

Matt Cardwell really spent a lot of time explaining CNC theory to me and

everything that applied to their systems.

I have ended up having bought a fair amount of Cognisys components. It’s

super high quality and extremely lightweight for the application.

Matt is one really smart guy. I very much appreciate his technical

advice

encouragement and support with this project. Matt suggested

remediations to diminish resonance in the systems.

I'm using heavy gear boxes that I adapted to accept

large Nema 23 hybrid stepper motors,

with intermediary gear reducers. I created a special "sandwich" of

rubber gaskets and aluminum plates to help

reduce mid-band resonance. This design very closely resembles the

design/build I did with OPRA in the early nineties.

The through-shaft holds strong, lightweight aluminum arms. With

close to 180 degrees of travel they enable

all the movement I need in that direction. I use Cognisys

Stackshot extended rails in certain situations.

This is currently the main body of RC-ACR II. The heavier gear heads

and motors hold the gear and cameras well.

In a studio session, the motors don't overheat even when the robot is

operating for several hours.

There is a price to be paid however: it's NOT portable. No hiking

with this kit.

RC-ACR II by Mark Lindquist, late 2015 studio iteration - iphone photo

I use various heads with RC-ACR II for different effects.

RC-ACR II's base allows for quick changeouts.

This particular head is extremely smooth and is often used on the

"portable robot". I found an

ancient inertial damper (blue) on ebay that was in brand new condition

and it just worked beautifully.

This is a Nema 23 hybrid stepper

motor with an intermediary gear reducer

and a custom bracket I made for it. The camera is attached to the shaft

via a custom

machined fitting I made that accepts large machine nuts. I try to

use available manufactured parts and repurpose

them whenever possible. Since the robotic camera components are

interchangeable, RC-ACR I, and II can be

reconfigured, or additional robots can be configured for other

photographic purposes.

Since I use two Cognisys controllers I can assign 6 axes

arbitrarily to any motor/gearhead combos.

I have another set of Nema 23 gear head and arms that forms its

own robot or may be used to augment this iteration of RC-ACR II.

Cognisys Inc., Stackshot 3X 3-axis controller.

I very much appreciate the Cognisys controllers. With the two of

them in tandem, I can run

automated routines or simply position the camera. With this

system, which can be automated or static,

I can mimic handheld movements created over the years or have the

"ultimate tripod" moving components for positioning or panning, etc.

The StackShot 3X comes with watertight cables and a battery pack option.

All in all, it's a really tight, very well designed system for either

studio or field work.

Former (and occasional) studio assistant, photographer John McFadden

suggested I look into

a remote camera control system called CamRanger. John has an

encyclopedic knowledge of

camera equipment. A former photographic assistant to Greg Silker

(who does photography for Minn kota and Ranger), John is always current on

the

most recent advances in photographic gear. John's suggestion to use

CamRanger

has proved invaluable. He and I worked together on OPRA years

after it was built retrofitting a brake to the central turntable. I

always appreciate John's help.

Lindquist Studios Former Assistant, Photographer John McFadden -

Photo: Mark Lindquist

I use CamRanger almost exclusively, tethered wirelessly to my Nikon

cameras.

CamRanger's receiver mounts to the camera via a hotshoe mount I devised.

The beauty of CamRanger is that it works on several platforms. I

use it with my iPad.

It enables almost complete control of the camera wirelessly and works

off its own wi-fi.

Gradually, I’m beginning to get a handle on how the camera operates as

an end-effector on the robot with repetitive, programmable routines.

I’m beginning to understand the possibilities and the limitations of the

system.

Just as I accepted sympathetic vibration in some of the lathes I built

and incorporated the "defects" into the designs,

I am doing the same here, since backlash is heightened by weight, and

unavoidable within my budget.

Early on in my work as an artist, I developed a philosophy of not

fighting the materials, but rather accepting them.

The problems I cannot overcome in my designs and builds of the machines

become integral to the

designs of the art work. The irregularities represent a "gift of

the machine" in this philosphy.

The art I make comes from techniques developed over 20 years of working

with

motion blur and over 45 years working as a professional photographer.

That history has enabled me to know what to look for in designing and

building my robotic systems.

In my current work, I use hand-held techniques developed over 2 decades

in concert with

my new robotic camera. I don't just press a button either on the

camera or the camera robot.

My robotic systems are simply additional tools in the process of making my art.

The process involved in making images is painstaking and unforgiving.

Abstract Image made in part by using Mark Lindquist's CNC

robot RC-ACR II

In-camera creation - single exposure jpeg. RAW retained for

future editing.

Copyright ©

Lindquist Studios 2015/2016

All Rights Reserved

The experience of designing and building the current working model has

been rewarding and uniquely challenging.

I’m also working on 2 heavier duty models that I began building before

RC-ACR I, and hope to finish someday.

DROVER is a portable robot for field use that I'm working on.

It is operated by wheelchair

motors and controllers.

It’s still in the prototype stage.

Stepper motor control is a tricky business. Fortunately for

me, the Cognisys controllers enable usage of stepper

motors without having to go through a program involving a keyboard and

programming, There are

keypad strokes and a kind of programming, but not as complicated as CAD

systems.

By "tweaking" the controls, I'm able to change the characteristics of

the motors

which has a profound impact on the resultant images.

The miniaturization of my large robots has been extremely difficult and

expensive.

Without the history of having built my early woodworking robots

from

new

and salvaged materials this project would not have been possible.

Abstract Image made in part, with Mark Lindquist's CNC

robot RC-ACR II, January, 2016.

In-camera creation - single exposure. RAW image, minimally edited in

Photoshop.

Copyright ©

Lindquist Studios 2015/2016

All Rights Reserved

Mark Lindquist with his robot OPRA, Lindquist Studios, 2007

Photo: John McFadden

Article © Mark Lindquist 1/23/2016

All Rights Reserved

Copyright ©

Lindquist Studios 2016

All Rights Reserved

Photos: Mark Lindquist, John McFadden, Roger Paph

Visit:

http://cognisys-inc.com

http://picengrave.com

http://johnmcfadden.net

|